A version of this interview appeared in French at http://revueperiode.net/le-role-de-la-prison-dans-la-lutte-des-classes-entretien-avec-ruth-w-gilmore/

Clément Petitjean: In Golden Gulag, you analyse the build-up of California’s prison system, which you call “the biggest in the history of the world”. Between 1980 and 2007, you explain that the number of people behind bars increased more than 450%. What were the various factors that combined to cause the expansion of that system? What were the various forces that built up the prison industrial complex in California and in the US?

Ruth Wilson Gilmore: Sure. Let me say a couple of things. I actually found that description of the biggest prison building project in the history of the world in a report that was written by somebody whom the state of California contracted to analyse the system that had been on a steady growth trajectory since the late 1980s. So it’s not even my claim, it’s how they themselves described what they were doing. What happened is that the state of California, which is, and was, an incredibly huge and diverse economy, went through a series of crises. And those crises produced all kinds of surpluses. It produced surpluses of workers, who were laid off from certain kinds of occupations, especially in manufacturing, not exclusively but notably. It produced surpluses of land. Because the use of land, especially but not exclusively in agriculture, changed over time, with the consolidation of ownership and the abandoning of certain types of land and land-use. It also produced surpluses of finance capital – and this is one of the more contentious points that I do argue, to deadly exhaustion. While it might appear, looking globally, that the concept of surplus finance capital seemed absurd in the early 1980s, if you look locally and see how especially investment bankers who specialised in municipal finance (selling debt to states) were struggling to remake markets, then we can see a surplus at hand. And then the final surplus, which is kind of theoretical, conjectural, is a surplus of state capacity. By that I mean that the California state’s institutions and reach had developed over a good deal of the 20th century, but especially from the beginning of the Second World War onwards. It had become incredibly complex to do certain things with fiscal and bureaucratic capacities. Those capacities weren’t invented out of whole cloth, they came out of the Progressive Era, at the turn of the 20th century. In the postwar period they enabled California to do certain things that would more or less guarantee the capacity of capital to squeeze value from labour and land. Those capacities endured, even if the demand for them did not. And so what I argue in my book is that the state of California reconfigured those capacities, and they underlay the ability to build and staff and manage prison after prison after prison. That’s not the only use they made of those capacities once used for various kinds of welfare provision, but it was a huge use. And so the prison system went from being a fairly small part of the entire state infrastructure to the major employer in the state government.

So the reason that I approached the problem the way I did is because I’m a good Marxist and I wanted to look at factors of production, but also to make it very clear – and this has to do with being a good Marxist – that these factors of mass incarceration, or factors of production, didn’t have to be organised the way they were. They could have become something else. Therefore I begin with the premise that prison expansion was not just a response to an allegedly self-explanatory, free-floating thing called crime, which suddenly just erupted as a nightmare in communities. And indeed, in order to think about crime and its central role in California’s incarceration system, I studied, like anybody could have, what was happening with crime in the late 1970s and early 1980s. And not surprisingly, it had been going down. Everybody knew it. It was on front pages of newspapers that people read in the early 1980s, it was on TV, it was on the radio. So if crime did not cause prison expansion, what did?

CP: So what was happening more specifically in California? How did those surpluses come together to create this mass prison system?

RWG: Well, they came together politically. In a variety of ways. During the 1970s, the entire US economy had gone through a very long recession. It was the time when the US lost the Vietnam war, when stagflation became a rule rather than an unimaginable exception — which is to say there was both high unemployment and high inflation. In that context, throughout the United States, people who were in prison had been fighting through the federal court system concerning the conditions of their confinement, the kinds of sentences that they were serving, and so forth. Many of these lawsuits were brought by prisoners on their own behalf. They slowly made their way through the courts. Eventually, in California but in many other states too, in the late 1960s and again in the mid-1970s, the federal courts told the state prison system: “Do something about this, because you’re in violation of the Constitution.” At first it might seem that the Vietnam War, stagflation and the violation of prisoners’ constitutional rights are unrelated. But indirectly, building prisons and using crime became a default strategy to legitimise the state that had become seriously delegitimised due to political, military, and economic crises. Prison expansion became a way for people in both political parties to say: “The problem with the United States is there is too much government. The state is too big. And the reason people are suffering from this general economic misfortune is because too much goes to taxes, too much goes to doing things that people really should take care of on their own. But if you elect us, we will get rid of this incredible burden on you. There is something legitimate we can do with state power, however, which is why you should elect us: we will protect you from crime, we will protect you from external threats.” And people were elected and re-elected on the basis of these arguments. Again, even though everybody knew that crime was not a problem. It’s pretty astonishing to me. I lived through this period and went back and studied it later. I found in the California case — and I currently have students who are studying other states — we keep coming across similar patterns: economic crisis, federal court orders, struggles over expansion, increased role of municipal finance in the scheme of prison expansion.

In California, people who had come up through the civil service, working in the welfare department, or working in the department of health and human services, eventually were recruited to work on the prison side because they had the skills to manage large-scale projects designed to deliver services to individuals. And they brought their fiscal and bureaucratic capacities over to the prison agency in order to help it expand and consolidate. We actually see the abandonment of one set of public mandates in favour of another – of social welfare for domestic warfare, if you will. And I can’t say, nor should anybody, that the reason all this happened was because of a few people who had bad intentions distorted the system. But rather we can see a systemic renovation in the direction of mass incarceration: starting in the late 1970s, when Jerry Brown, a Democrat, was governor of California, as he is now; then taking off enormously in the 1980s under Republican regimes; but never going down. It didn’t make any difference which party was in power. And the prison population did not begin to go down until elaborate and broad-based organising combined with a long-term federal court case (again!) compelled system shrinkage in the last several years.

CP: In the book, you argue that prisons are “catchall solutions to social problems.” Would you say that the rise of the prison industrial complex illustrates, or means, deep transformations of the American state, and marks the dawn of a new historical period for capitalism, one where incarceration would be not only the legitimate but the only way of dealing with surplus populations?

RWG: Honestly, fifteen years ago, I would have said yes. Now, I say “pretty much, but not absolutely yes”. Because it’s almost worse than the way you framed the question. Rather than mass incarceration being a catchall solution to social problems, as I put it, what has happened is that that legitimising force, which made prison systems so big in the first place, has increasingly given police – including border police — incredible amounts of power. What has happened is that certain types of social welfare agencies, like education, income support, or social housing, have absorbed some of the surveillance and punishment missions of the police and the prison system. For example in Los Angeles, a relatively new project, about ten years old, focuses on people who live in social housing projects. Their experience has been shaped by intensive policing, criminalization, incarceration and being killed by the police. Under the new project they have opportunities for health, tutoring for children, all kinds of social welfare benefits if and only if they cooperate with the police. In the book Policing the Planet, my partner and I wrote a chapter that goes into rather exhaustive details about that case.

CP: Would you say that those shifts herald a new historical period for capitalism?

RWG: This is a tough question, as you know, for a bunch of reasons. One is that we’ve all learned to lisp: everybody used to say “globalisation,” now it’s “neoliberalism,” and people are more or less talking about the same thing. My major mentor in the study of capitalism is the late great Cedric Robinson, who wrote an astonishing series of books, but the one that completely changed my consciousness is Black Marxism. Robinson argues that capitalism has always been, wherever it originated (let’s say rural England), a racial system. So it didn’t need Black people to become racial. It was already racial between people all of whose descendants might have become white. Understanding capitalism this way is very productive for me when thinking about the present. One issue is what’s happening with racial capitalism on a world scale. A second issue has to do with particular political economies, especially those that are not sovereign, like the state of California: how does political-economic activity re-form in the context of globalisation’s pushes and pulls? Certainly, California’s economy continues to be big. It moves up and down a little bit, but if it were a country, it would be in the top seven largest economies. However, the mix of manufacturing, service and other sectors has changed over time. There’s still a lot of manufacturing in the state, although it tends to be more value-added, lower-wage manufacturing, sweatshops and so forth. And far less steel, and producer goods, and consumer durables.

How, then, should we analyse in order to organise in places like California, New York, Texas, with their various and variously diverse economies, characterised by organised abandonment and organised violence? How can we generalize from the racist prison system to a more supple perception of racial capitalism at work, to understand and intervene in places where states no less than firms are constantly trying to figure out how to spread capital across the productive landscape in ways that will return profits to investors as quickly as possible? The state keeps stepping in while pretending it’s not there. And here I’m not talking about private prisons, which are an infinitesimal part of mass incarceration in the US, nor of exploited prisoner labour, which also doesn’t explain much about the system’s size or durability (which, as we’ve already seen, is vulnerable). Rather, I am talking about how unions that represent low to moderate wage public sector workers, which have a high concentration of people of colour as current and potential members, might join forces with environmental justice organisations, biological diversity/anti-climate change organisations, immigrants’ rights organisations, and others to fight on a number of fronts group-differentiated vulnerability to premature death — which is what in my view racism is. And if that’s what racism is, and capitalism is from its origins already racial, then that means a comprehensive politics encompassing working and workless vulnerable people and places becomes a robust class politics that neither begins from nor excludes narrower views of who or what the “working class” is.

CP: In the book, you develop a critical perspective strongly influenced by David Harvey’s critical geography. What does this perspective reveal specifically about mass incarceration?

RWG: I became a geographer when I was in my 40s because it seemed to me, at least in the context of US graduate education, it was the best way to pursue serious materialist analysis. There are so few geography PhD programs in the United States. And I’d been thinking that I was going to train in planning because it seemed the closest to what I wanted to do: to put together “who”, “how,” and “where” in a way that did not float above the surface of the earth but rather articulated with the changing earth. I actually stumbled into geography. I happened to come across Neil Smith at a Rethinking Marxism conference and was really taken by his work; not only had I not thought about geography, I hadn’t taken a geography course for three decades, since I was 13. So at the last minute, instead of mailing my application to the planning department at Rutgers, I mailed it to the geography department. And the rest is kind of history. Enrolling in geography brought me into the world of Harvey’s historical geographic materialist way of analysing the world. I took very seriously what I learned from David, what I learned from Neil and a few other people, and tried to build on it, having already had a long informal education with people like Cedric Robinson, Sid Lemelle, Mike Davis, Margaret Prescod, Barbara Smith, Angela Davis, and many others. And I think that had I not been trained in geography, or beguiled by geography, maybe, I would not have thought as hard as I did about, for example, urban-rural connections – their co-constitutive interdependencies. And I know I wouldn’t have thought in terms of scale — not scales in the sense of size, but in terms of the socio-spatial forms through which we live and organise our lives, and how we struggle to compete and cooperate. And I certainly would not have conceptualised mass incarceration as the “prison fix” had I not read David’s Limits to Capital and thought about the spatial fix as hard as I could. We’re colleagues, now, David and I. We enjoy working together and debating toward the goal of movement rather than having the last word.

CP: Can you elaborate on what you mean by “prison fix” compared to Harvey’s “spatial fix”?

RWG: What I mean in my book is that the state of California used prison expansion provisionally to fix – to remedy as well as to set firmly into space – the crises of land, labour, finance capital and state capacity. By absorbing people, issuing public debt with no public promise to pay it down, and using up land taken out of extractive production, the state also put to work, as I suggested earlier, many of its fiscal and organisational abilities without facing the challenges that were already mounting when the same factors of production were petitioned for, say, a new university. The prison fix of course opened an entire new round of crises, just as the spatial fix in Harvey displaces but does not resolve the problem that gave rise to it. So in the case of communities where imprisoned people come from, we have the removal of people, the removal of earning power, the removal of household and community camaraderie, you name it – all of that happened with mass incarceration. In the rural areas where prisons arose we can chart related de-stabilisations: rather than, as many imagine, rural prison towns acquiring resources displaced from urban neighbourhoods, the fact is the two locations are joined in a constant churn of unacknowledged though shared precarious desperation – which was the basis on which some of the organising I described above took form. In other words infrastructure materially symbolised by the actual prison indicates the extensively visible and invisible infrastructure that connects the prison and its location by way of the courts and the police, the roads for families to visit and goods and incarcerated people to travel, back to the communities of origin expansively incorporating the entire intervening landscape. One of the things I tried to do in the book, framing it with two bus rides, was to give people a way of thinking about what I’ve just said that’s more viscerally poignant. Thinking about the movement across space and the movement through space gives us some sense of the production of space.

The purpose of Golden Gulag was not to make people say “Oh my God, we’ve all been defeated!” but rather to say “Wow, that was really big, and now I can see all the pieces. So perhaps instead of thinking there’s nothing to be done, what I recognise is there’s a hundred different things that we could do. We can organise with labour unions, we can organise with environmental justice activists, we can organise urban-rural coalitions, we can organise public sector employees, we can organise low-wage, high-value-added workers, who are vulnerable to criminalisation. We can organise with immigrants. We can do all of these things, because all of these things are part of mass incarceration.” And we did all that organising!

CP: That’s a perfect transition to another set of questions about organising against mass incarceration. Are there resistance movements within prisons comparable to what happened in the 1970s, with the 1971 Attica uprising for instance?

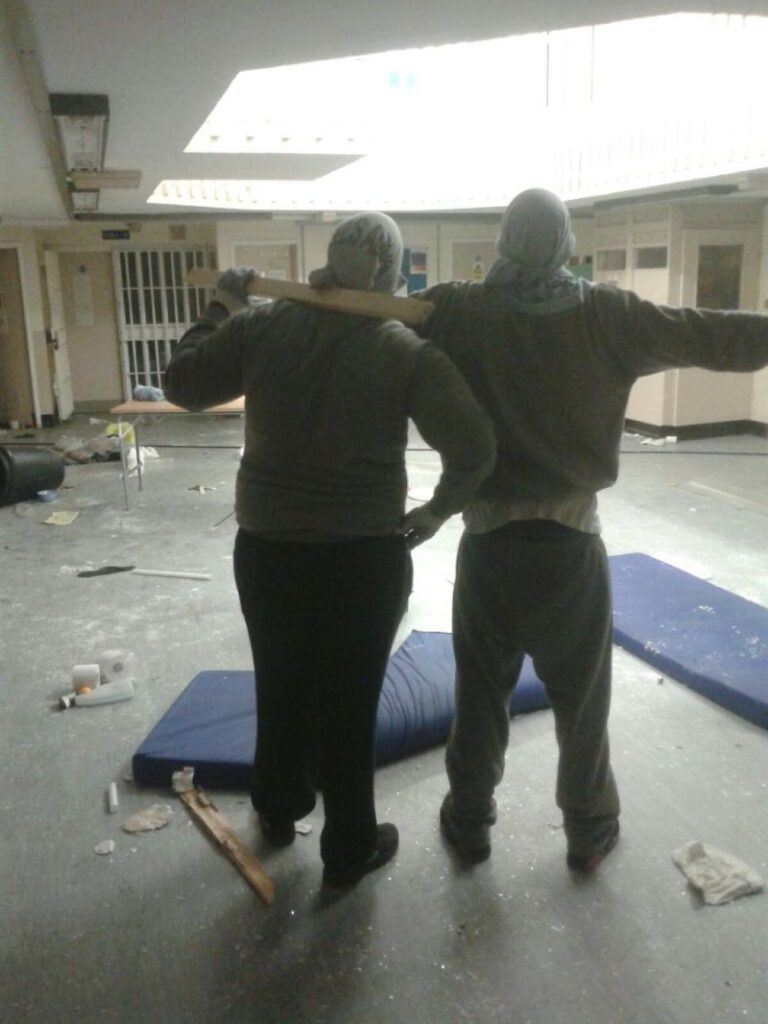

My area of expertise doesn’t happen to be on that. Orisanmi Burton is someone who is doing fantastic research on that question. Of course, one of the things that’s happened in California prisons, particularly the prisons for men, is that their physical design, as well as the design of their management system, were deliberately aimed by the Department of Corrections, starting in the late 1970s, to undermine the possibility of the kind of organising that had characterised the period from the early 1960s to the mid-1970s. Especially the ones called 180s, or level 4: those are the high-security prisons. They’re not panopticons, but prisoners can’t evade being under surveillance. There have been not only automatic lockdowns, but also the reduction of education and other in-prison programs, even places where people in prison can gather, such as day rooms, classrooms, gyms, places where prisoners could do the time with some however modest ongoing sense of self. All of the design changes were intended to undermine prisoner organising and solidarity.

One hugely notorious thing that happened in the California system in particular in the late 1970s, that may or may not have happened in other systems, is that the Department of Corrections, was experimenting with ways to keep prisoners from developing solidarity with each other and against the guards. In the early 1970s, California prisoners had notoriously declared “Every time a guard kills one of us, we’re going to kill one of them until they stop killing us.” And there were seven incidents over some years. A guard killed a prisoner, prisoners killed a guard. Not necessarily the guard who killed the prisoner, but somebody died because somebody died. So the department, right before its big expansion began, was trying to figure out what to do. And it came up, not surprisingly, with a solution that was designed to foster inter-prisoner distrust. The managers declared that certain categories of prisoners belonged to certain ethnic or regional gangs, and then fomented discord between the gangs. In a time when desegregation was becoming the law of the land, the Department of Corrections started segregating people in prisons according to the gangs and then to racial and ethnic groups. This is all well documented, there are case files and lawsuits, and an incredible archive, still to be thoroughly read and written about. And there were countless hearings about this practice throughout the 1990s. I sat through hours of testimony, in which the Department insisted, and has until this day: “No, we were just responding to what objectively existed.” Whereas others who testified, including former prison wardens, said: “No, this didn’t exist: you made it. You created it.”

What the Department “created” led to development of something called the Security Housing Unit (SHU), which is effectively a prison within the prison. The first one in California opened in 1988 and the second in 1989. In the latter, called Pelican Bay State Prison, people in the SHU had staged several hunger strikes beginning in 2013. And some of the people in that unit, segregated according to their alleged gang affiliation, some of whom had been in that prison within the prison for more than twenty years, had accepted and projected the rigid ethnic, racial, and regional differences as meaningful and immutably real. But as they were trying, as individuals, to sort out a way for them to get out of the prison in the prison and go back to the general prison population, they became increasingly aware of what had happened historically, a dire reform of which they were the current expression. And so in recent years, these people in four “gangs” eventually declared that the only way to solve the problem inside was, to use their word, to end the hostility between the races. Which is an astonishing thing. I’ve been inside a lot of prisons, including Pelican Bay. And the transformation of consciousness from what I learned from interviewing people in prisons for men about their conditions of confinement in the early 2000s compared with the organising and analysis that emerged in the last five or so years is astonishing.

I also want to add something about the prisons for women. In the prisons for women, the level of segregation was never as high — to the extent, for example, that they had not separated out people who were doing life on murder and people who were doing a year on drugs. Whereas in a prison for men people are segregated according to custody level (what they are serving time for having done) plus segregated in a number of other ways including race and ethnicity. And so, in part because of the social and spatial organisation of the prisons in the period that featured the crackdown on organising in prisons for me, there was a high and growing level of organising among the people in prisons for women. So during the last fourteen or fifteen years, as the state of California was trying to build fancy new so-called “gender responsive” prisons for women – to allow mothers to be locked up with their kids, for example — people inside those prisons, however they identified in terms of gender, wrote and signed “Don’t do this for us, because that’s just going to expand capacity to lock people up. It’s not going to make our lives better.” Three thousand people did that organising in prisons for women, and their self-determination and bravery occurred at great personal risk to themselves because locked-up activists are wholly at the mercy of guards and prison managers.

CP: What about the organising outside of the prisons? And in particular in communities directly affected by mass incarceration?

RWG: The organising outside has been quite rich and varied over the years. In my experience, some of which I write about in a new chapter to the upcoming second edition of Golden Gulag, people who at the outset started doing work on behalf of one person in their family or even maybe two people in their family, thinking this was an individual, or greatest scale, household problem, came to understand through their experiences — working with others, mostly women, most of whom were mothers — the political dimensions of what they originally encountered as a personal, individual, and legal problem. That’s one kind of organising that has persisted for many years now, 25 years of more. There’s also the organising that we, meaning the groups Critical Resistance and California Prison Moratorium Project, helped to foster between urban and rural communities, under a variety of nominal issues which I described earlier: biological diversity (we took up on behalf of the lowly Tipton kangaroo rat) but also environmental justice (air quality, water quality for instance). We managed to develop and wage campaigns bringing people together across diverse issues and diverse communities in rural and urban California, so that they could recognise each other as probable comrades rather than presumed antagonists. And that has happened over and over again.

Going back to the fact that the number of people in prisons in California has gone down in recent years: the public explanations for that, the superficial or above-the-surface explanation, is that in 2011 the state of California lost yet another lawsuit, Brown v. Plata, also called “Plata/Coleman,” and was ordered to reduce the number of people held in the Department of Corrections’ physical plant (33 prisons plus many camps and other lockups). The federal lawsuit demonstrated that approximately one person in prison a week was dying of an easily remediable illness because of medical neglect. During the two decades between the beginning of the legal campaign and its resolution, some of the original litigants had long since died. Ultimately, the right-wing Supreme Court of the United States (the court that handed George W. Bush the presidency in the year 2000) could not deny the evidence. There were just too many bodies. In its final judgment that court agreed with lower court rulings, affirming that California could not build its way out of its problem.

But the question that few people who have followed this story ever asked themselves is “How come California, that had been opening a prison a year for 23 years, suddenly slowed down to almost a halt and only opened one prison between 1999 and 2011? And the answer is all that grassroots organising that I described earlier. We stopped them building new prisons. We made it too difficult. And we showed in our campaigning that whenever the department built a new prison, allegedly to ease crowding, the number of people in prison jumped higher than the new buildings could hold. The new relationships on the ground, organised by prison abolitionists – though the vast majority of participants themselves were not necessarily abolitionist – compelled these courts, who had never summoned any of us as serious witnesses for anything, to say that California could not build its way out of its problem and that it had to do something else. So now a lot of anti physical plant expansion activity in California has shifted to jails, not prisons. (Jail is where someone is held pending trial or if their sentence is only a year or less. Prison is where someone is sent to serve a sentence for a year and a day or more.) The jails are now expanding because once California complied with the Supreme Court ruling, the state, in order to reduce the number of people it locks up, made resources available to the lower political jurisdictions — the counties — to do whatever they wanted in exchange for retaining people convicted of certain crimes locally rather than sending them to state custody. (This adjustment is called “realignment.”) The counties could have taken those resources and said to convicted people “Go home and behave yourselves.” They could have taken the resources and changed guidelines for prosecutors so there would be fewer convictions. They could have put the resources into schools or healthcare or housing. But – and this gets back to the nagging question of state capacity and legitimacy — a little more than half of the state’s 58 counties have thus far decided to build new jails. And then we see in reverse the phenomenon I discussed earlier, about welfare state agencies absorbing surveillance and punishment agencies. The sheriffs, who run the jails, now insist that they need more and bigger jails for reasons of health: “We have to supply mental health care and counseling to troubled people. We need to deliver social goods, and the only way we can do it is if we can lock people up.” So the new front is fighting against “jails-instead-of-clinics,” “jails-instead-of-schools,” and so on. The work brings new social actors into the mix, and, as we discussed earlier, it enables the broadest possible identification of purpose in class terms.

To give you a few other examples of the kinds of solidarity that we managed to bring into action over time in California, there was a prison that was supposed to have opened in 2000 but we slowed it down. We didn’t manage to stop it, but as I said, after opening a prison a year up to 1998, there were none opened between 1999 and 2005. That prison was scheduled for construction by a member of the Democratic party who had just been elected governor, and he was paying back the guards’ union, who had given him almost a million dollars to help with his campaign. So then we got busy and organised as many different ways as we could. And one of the ways we could organise, it turned out, was with the California state employees association, which is part of an enormous public sector union in California. And they represent all kinds of workers in the prisons except the guards, because the guards have their own stand-alone union. And much to our surprise, the members of state employees union were willing to go up against the guards and oppose that prison. When they finally agreed to meet with the abolitionists they said: “Look. The guards get whatever they want. What we do, as secretaries, school teachers, locksmiths, drivers, mechanics gets squeezed more and more. We see the lives of the people in custody getting worse and worse, with no hope for getting back to a normal life when they get out — as most people do. And the union that we’re part of represents people who work in the public sector, in housing, healthcare, so on and so forth, in the cities and counties as well as at the state. So if we recognise who our membership is and what they do, there’s no reason for us to support this prison. Even if we might lose a few members who would have the jobs in the new prison, there’s more to our remit, as a public sector union.” That completely surprised me, and for a heady political moment we had half a million people throughout California calling for a prison moratorium. It’s hard to keep those kinds of political openings lively, but it lasted long enough to interrupt the relentless schedule that the prisons in California had been on since the early 1980s.

CP: From an outsider’s perspective it seems that the Black Lives Matter movement gave a new impetus to debates around prison abolition in radical circles. What does it say about the history of the abolition movement? What’s the current balance of forces? What do strategic debates look like?

It’s true that #Black Lives Matter has got people thinking about and using the word “abolition”. That said, the abolition that they have helped put into common usage is more about the police and less about the prisons. Although of course there is a connection between the two. It’s been amazing to me and many of my comrades to see left liberal politicians, or magazines like The Nation or Rolling Stone, seriously ask whether it is time to abolish the police. The ensuing debates tend to be the obvious ones: insofar as abolition is imagined only to be absence – overnight erasure – the kneejerk response is “that’s not possible”. But the failure of imagination rests in missing the fact that abolition isn’t just absence. As W.E.B. Du Bois showed in Black Reconstruction in America, abolition is a fleshly and material presence of social life lived differently. Of course, that means many who are abolition-friendly falter at what the practice is. All the organising I’ve described in our conversation is abolition – not a prelude, but the practice itself. There was a recent attack on abolitionists by some historian who decided, without studying, that abolitionists are a deranged theology. He knew a little, for example, about the Brown v. Plata case, but zero about the on-the-ground moratorium organising that realised the Plata/Coleman theory (“overcrowding”) as sufficient cause for which the remedy would not be more of the same. Abolition is: figuring out how to work with people to make something rather than figuring out how to erase something. Du Bois shows, in exhaustive detail, both how slavery ended through the actions and organised activity of the slaves no less than the Union Army, and, since slavery ending one day doesn’t tell you anything about the next day, what the next day, and days thereafter, looked like during the revolutionary period of radical Reconstruction. Abolition is a theory of change, it’s a theory of social life. It’s about making things.

CP: What does the central role of mass incarceration in maintaining the status quo imply in terms of class struggle strategies? Do anti-incarceration struggle and abolition organising play a more strategic role today?

RWG: Here’s a way of thinking about that in the US context. In the United States today, there are about 70 million adults who have some kind of criminal conviction — whether or not they were ever locked up — that prohibits them from holding certain kinds of jobs, in many types of jobs. In other words, it doesn’t make any difference what you allegedly did: if you’ve been convicted of something, you can’t have a job. So just take a step back and think about that for a second, just in terms of sheer numbers. If we add the number of people who are effectively documented not to work, with the additional 7 or 8 million migrants who are not documented to work, the sum equals about 50 percent of the US labour force — mostly people of colour, but also 1/3 white. Half the US labour force. So it seems that anti-criminalisation and the extensive and intensive forces and effects of criminalisation and perpetual punishment has to be central to any kind of political, economic change that benefits working people and their communities, or benefits poor people, whether or not they’re working, and their communities. This should be a given, but often it’s not. In part that’s because “mass incarceration” has, unfortunately but for understandable reasons, come to stand in for “this is the terrible thing that happened to Black people in the United States.” It is a terrible thing that happens to Black people in the United States! It happens also to brown people, red people … and a whole lot of white people. And insofar as ending mass incarceration becomes understood as something that only Black people must struggle for because it’s something that only Black people experience, the necessary connection to be drawn from mass incarceration to the entire organisation of capitalist space today falls out of the picture. What remains in the picture seems like it’s only an anomalous wrong that seems remediable within the logic of capitalist reform. That’s a huge impediment, I think, for the kind of organising that ought to come out of the various experiments in worker and community organising that can produce big changes. Everything is difficult in the US right now, for all the obvious reasons I won’t waste space on now. That said, I look with hope for all indications of ways to shift the debate and organising. The answer for me is to consider in all possible ways how the preponderance of vulnerable people in the US and beyond come to recognise each other in terms not just of characteristics or interest, but more to the abolitionist point and purpose.